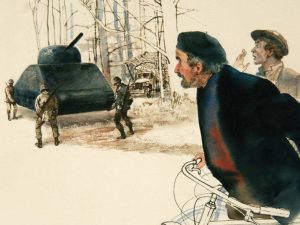

An American soldier in the Ghost Army captured this scene of French villagers in awe at the sight of U.S. troops lifting what appeared to be a Sherman tank, little knowing that the vehicle was an inflatable prop.

In 2005, documentary filmmaker Rick Beyer became fascinated with the history of the “Ghost Army,” a top-secret tactical deception unit charged with tricking the Nazis during World War II whose work had only recently been declassified. Among the veterans of that unit was Jim Steg, the subject of a retrospective on view at NOMA through October 8. Steg’s wartime sketches of refugees he encountered on his tour of duty are on display as part of an exhibition that spans the renowned New Orleans printmaker’s fifty-year career. Beyer’s film will be shown at NOMA on Friday, September 1, at 7 p.m., and he will present a lecture on Wednesday, September 27, at 6 p.m.

How did the Ghost Army come to be?

The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, also known as the “Ghost Army,” was a deception unit that operated in the European Theater of Operations in World War II, and they used inflatable tanks and sound effects and illusions to fool the Germans. They did this in 21 different battlefield deceptions, starting shortly after D-Day and going to the end of the war. One of the interesting aspects of the story is that the unit selected to handle visual deception, the 603rd Camouflage Engineers, was loaded with artists. It wasn’t everybody in the unit, but it was a significant percentage of people in the unit, somewhere between 25 and 50 percent. Of course, one of those artists was Jim Steg.

How was the Army able to recruit artists?

They had connections at art schools. In some cases, art schools were doing camouflage programs because it was wartime and people were trying to find a way to contribute. The Pratt Institute in New York and NYU and others did camouflage classes, and that was one way that they recruited artists. Of course, people often were looking for a way to use their artistic talent and not end up being in the infantry, which is both not using your talents and also more dangerous than any other branch. So people were looking for the opportunity, as well. The Army had a need, people had an interest, and that’s how this unit came together.

Jim Steg emerged from his tour of duty to become a professional artist. What other veterans of the Ghost Army went on to pursue artistic careers?

Many veterans of this unit went on to pursue artistic careers. We probably would start that list with fashion designer Bill Blass. We might put in there painter and sculptor Ellsworth Kelly. We might add wildlife artist Arthur Singer. We could put on there photographer Art Kane, who took that very famous picture of all the jazz musicians on the stoop in Harlem, and other guys, who became illustrators: Victor Dowd, Arthur Shilstone, Bill Sayles. There’s another fashion designer, Ed Nardiello. There were architects. Gil Seltzer was one. Creative people went on to do set design in Hollywood or designing store windows at big department stores.

Even after the war the Ghost Army remained top-secret for nearly fifty years. Why?

Some people made efforts to declassify it, but the Pentagon really clamped a lid down on it, and they wanted to keep it secret. It started coming out in the ‘80s and was really fully declassified by the ‘90s. One reason why it was kept secret for so long might be because it worked, and the military wanted to use some of these techniques for possible use against, say, the Russians, if the Cold War had turned hot. If you reveal all the great deceptions, then the next time you go to war, people are going to be looking for those deceptions. It’s just the same way that in football, people look at the game films from the previous games to see what your tendencies are, so you don’t want to necessarily let the enemy—well potential enemies—know what all of your tendencies are. I think that’s probably why it was kept secret.

How did you become familiar with the Ghost Army?

I first came across this story 12 years ago. My former business partner introduced me to a woman whose uncle had served in the unit. She was very excited and felt that somebody ought to make a documentary about this. I went to what was, in essence, the last official reunion of this unit, in Washington in the fall of 2005. I started meeting the soldiers in the unit, started seeing their photographs, and I was looking at their artworks, and I really fell in love with the story. I mean, it’s a story about imagination and creativity in war. It’s not a bang-bang, shoot-emup story, but it’s a story about using your noggin to save lives. It’s a story in which artists have a role in helping win the war. This stuff is all kind of contrary to the expected, and I always love discovering the unexpected.

I fell in love with the people I met, some of the people who’d served in the unit and who’d had some of these artistic careers. Even the ones that I couldn’t meet because of they’d passed away, like Jim Steg, I got to look at their artworks and kind of see the war through their eyes. That’s an amazing thing all by itself, nevermind the deception mission. You have all these artists, who are, by the way, sort of like a traveling art school. They’re looking at each other’s work and learn from each other, and they are documenting the war and creating this unique documentation of their travels across war-torn Europe. …I have said many times, and I truly believe this, that this is one of the richest pieces of narrative material that I have ever come across.

Jim Steg: New Work remains on view in the Templemann Galleries through October 8, 2017. The retrospective of works by Steg includes his wartime sketches of refugees he encountered during his tour of duty. Learn more about Rick Beyer’s film and companion book at ghostarmy.org. Watch the trailer below.

On June 8, 2017, Louisiana Senator John Kennedy proposed federal legislation to honor veterans of the Ghost Army with Congressional Gold Medals. He mentioned the Steg exhibition in his speech.