The Forest of Fontainebleau became an experimental lab for picture-making in the nineteenth century. There, in this wilderness of varied terrain just 40 miles to the southeast of Paris, French artists created prints, drawings, oil sketches, photographs, and paintings of the forest that challenged traditional conceptions of landscape depiction. Their work signaled a shift from an understanding of landscape as classical, idealized, and controlled to immediate, natural, and uncontrollable. Fontainebleau, with its unkempt oak forests, craggy boulders, and vast, rocky plains, was the perfect subject for these artists. Indeed, by the mid-nineteenth century, Fontainebleau had become so entrenched as a landscape subject that the words “Fontainebleau” and “nature” were almost interchangeable in the French language. This exhibition reconsiders the role of prints, drawings, and photographs in the reinvention of nature in the Forest of Fontainebleau.

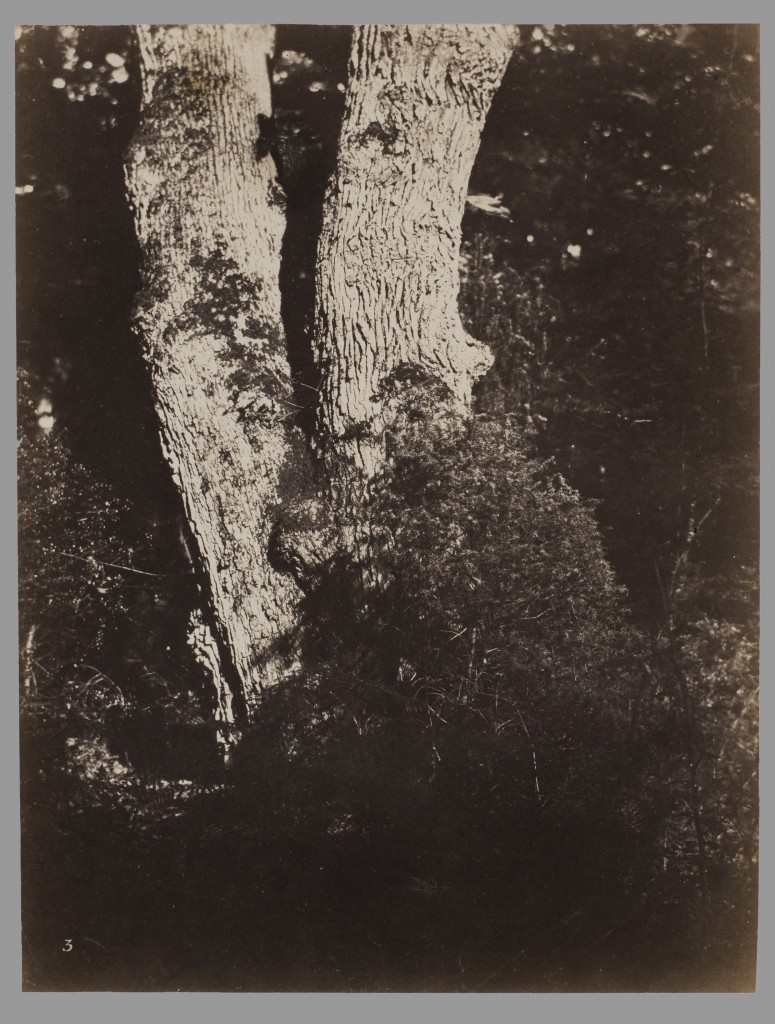

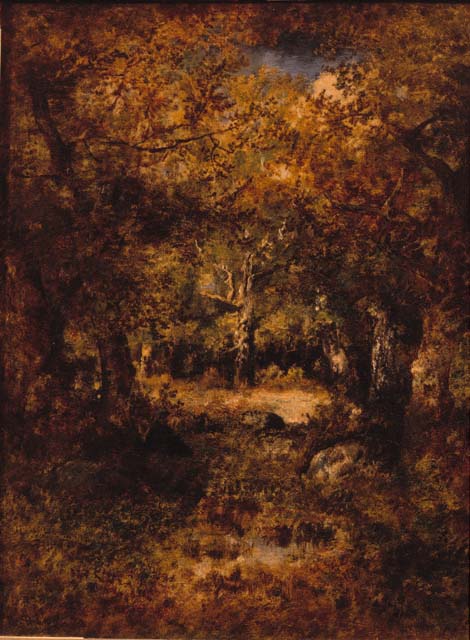

This reinvention of nature in the artistic world coincided with—and was informed by—debates about the earth’s timeline. Beliefs that the earth had been created, cataclysmically, about 6,000 years ago were countered by geologists who proposed that the earth had developed gradually, over millions of years. This rapid expansion of the earth’s age had a profound effect on the human psyche: suddenly, our presence on earth was ripped from a position of great authority and tossed into the chasm of the growing geologic record, a very small speck in the deep sea of time. At the same time, nature, an ever-evolving, grand old entity, became the subject of greater respect and admiration. In artistic terms, the concept of the “ideal landscape” no longer seemed to make sense. The belief that moving mountains and trees made for a better picture gave way to an approach that focused on nature as it was. Crooked trees, broken trunks, and moss-covered rocks became the new standard of beauty, as if to proclaim that nature, in all its imperfection, was already perfect.![]()

This new conception of nature demanded new artistic practices that allowed for greater spontaneity and immediacy. The laborious practice of painting in the studio, away from the subject, was cast aside in favor of making studies directly from nature. These studies took many forms: oil sketches made en plein air (“in the open air”), chalk and charcoal drawings of intimate details, photographs that capture the dappled light filtering through the trees, and clichés-verre (a hybrid process that is part printmaking, drawing, and photography). Although these works were initially thought of as preparatory studies for more finished paintings, ultimately they proved better suited to dynamic landscape compositions and were often exhibited as final works as well as lauded by critics.

Trees

1850s

Eugene Cuvelier

Scene in Fontainebleau

1904

Henri-Joseph Harpignies

At Fontainebleau

Circa 1850

Jules Dupre

Autumn (L’automne)

1872

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Pena

Sponsorts / Partners

This exhibition is made possible through a donation from an anonymous funder and a grant from the International Fine Art Print Dealers Association.

![]()