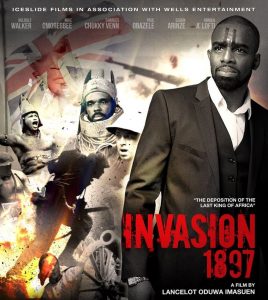

NOMA will host a film screening and roundtable discussion under the theme “Looking Closely at Social Conditions in Nigeria,” led by African Art Curator Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, on Friday, April 12, from 6 – 8 pm. The movie, Invasion 1897, was produced by Nigerian filmmaker Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen in 2014 and tells the story of a contemporary African scholar arrested fand put on trial or allegedly stealing artifacts in a London museum that had been looted by British colonizers in the Benin Kingdom nearly a century prior. The protagonist envisions himself in the battles that took place when these objects were stolen and brought to Europe. In advance of the discussion, Ezeluomba, a native Nigerian, spoke with NOMA Magazine about the themes presented in the film, and issues faced by Nigerian expats in the U.S.

What subjects do you plan to discuss at the roundtable panel?

After watching the movie, the idea is to take themes from the film and focus on very important social conditions that many Nigerians face, paramount among which is the current economic conditions that has led to a huge migration of a number of Nigerians, a diaspora, to Western nations. The movie, on its own, is a re-creation of the historic event of 1897 that led to the destruction of the Benin Kingdom. When the kingdom was destroyed, a significant number of the art objects were removed and taken to Europe and sold and later resold. They form the crux of African art history. We use that to see how these treasures of Benin came to the West and got scattered around, the same way the social conditions of Nigeria today has led to a huge number of individuals living in other countries. The roundtable will close in on this diverse group that has left Nigeria, and the predicaments that they face in the new environments where they find themselves.

Are Nigerians leading an effort to return these works of art?

The issue of repatriation has been going on for a long time. in 2017, French President Macron recently made a powerful statement about returning cultural property back to many African countries where they were removed by force. I was in elementary school when I first heard about the issue of repatriation. In 1977 there was a cultural festival held in Nigeria called FESTAC, a festival of arts and culture, and in a period leading up to the festival the Nigerian government had requested that a British museum loan them one of these objects for them to use as the backdrop of the whole festival. There was a lot of back and forth in that episode, and finally the object did not go to Benin, so the organizers had to make a replica. That started a larger debate — This is our property, why can’t we have access to it? And also, when Nigerian scholars started focusing on Benin, back home there were no institutions that held these objects. For you to be able to see these objects, you had to travel to far-away England. All of these instances led Nigerians to say, We own these, we must have access to them as well.

Along the line, some of the objects from the Benin Kingdom were returned, but the most significant were not. Among the objects that were returned, people who were working in the Ministry of Antiquities, caring for these objects, were caught removing them and selling them again. A significant British scholar in African art studies no longer with us, William Fagg, admonished in the late 1980s and early 1990s that if institutions are not created in Africa, returning these objects to their homelands would not make sense because the objects would only be given away.

What efforts are underway to make repatriation possible?

After President Macron made the declaration, the Benin people began to re-energize their voice, to cry for repatriation all over again. Now we have offshoots of groups that cut across academia and museums that are trying to create a system that works. The Benin Dialog Group is a conglomeration of some cultural institutions in Europe working with the king of Benin to create a rotation of art objects from European museums to Africa, so that some of the objects would come to Benin and be displayed for some time, followed by another batch, with return to Europe for conservation. A larger plan is to help the Benin people construct a quality museum in the palace of the king. I am in support of this because there must be infrastructure in place. Outright return does not make sense.

The museum culture in Africa is not what we have here in the US. If we can put all of the right pieces together, with European and American museums involved, to recreate the structures and staffing that can properly hold and display these objects, this could work. There have been efforts to create exhibitions that would travel to Africa, but the logistics have been very difficult and it may cost considerably more for the objects to travel.

If the scholars who are studying this material in Africa, if they are granted visas to go study in the countries where these objects are stored, it will make the process much easier. Many are eager to go, but they are stalled because they might not get visas.

Repatriation is complex because because when these objects left Africa, they came from pockets of autonomous kingdoms that were not nations as they are now drawn. If this Benin Dialogue Group is now returning these objects to Benin City, they have to go thorough the bureaucratic system that requires the federal government, the state government, and down to local institutions where the obi (town and local government) play a significant role. Nigeria was just a name and boundaries formed in 1914. In the midst of that complexity, some of us are trying to find a workable solution, because outright return does not make sense.

In what way does the movie emphasize these issues?

The movie show that objects that were looted from the kingdom of Benin should be accessible to a person from Benin wants to have access to them. It falls back to what I said initially. Some of us want to go study these objects in Western institutions but there are many restrictions. The filmmaker is trying to show that we should have access to it — a consciousness to acknowledge that we own it and if we want to have access to it, don’t stop us from doing that.

Panelists from the Association of Nigerians in New Orleans will include Reuben Amienoho, Alabor Derefaka, and Olu Ariwajoye, each representing a different regional group in Nigeria.

Watch the trailer for Invasion 1897 ((2014 | Rated PG-13 | 1 hour, 53 minutes)