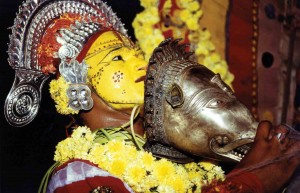

India, Karnataka, Panjurli (Boar’s Head) Bhuta Mask, 18th century, Bronze, New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Siddharth K. Bhansali, 97.853

Viewing a work of art at NOMA is a fundamentally different experience from seeing that same object in its original context. In a quiet museum gallery objects are presented in orderly fashion, appreciated for their aesthetic qualities and historical significance. It is important to remember, however, that some works were created as objects of devotion and the focus of rituals.

A particularly striking illustration of this variance can be seen in the Mask and Breastplate currently on view in the new gallery for the arts of India, on NOMA’s 3rd floor. These metal sculptures were created in south-western India, in the Kanara region of Karnataka where an ages-old religious practice, known as a bhuta cult, thrives. Bhutas are supernatural beings or divinized ancestor spirits that have been worshipped in parts of southwestern India since at least the 14th century. They take many forms, including boars, buffalo and ferocious manifestations of the god Shiva.

Anthropologists have documented the ways in which masks and breastplates functioned in bhuta rituals. At all-night ceremonies, dancers wear masks and breastplates as part of extraordinarily elaborate costumes (see photo gallery). The mask is surrounded by an aureole of flowers, and the breastplate is complemented by additional jewelry and brightly painted costume elements, including an arched backdrop and a broad skirt. The medium, through whom the bhuta communicates, accompanies the dancer and is similarly costumed. The medium invites a specific bhuta into himself, and that bhuta communicates through the medium, speaking through the mask. Bhutas dispense advice and counsel to the family sponsoring the ceremony, settle local disputes, as well as sing and tell stories.

Lisa Rotondo-McCord, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs and Curator of Asian Art