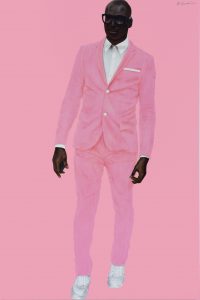

Barkley L. Hendricks, Photo Bloke, 2016, Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 in., Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, © Barkley L. Hendricks

As Prospect.4 comes to a close after a three-month run, Trevor Schoonmaker, the artistic director of New Orleans’ citywide triennial of contemporary art, reflects upon his friendship and collaboration with the late artist Barkley L. Hendricks. Hendricks’ paintings are on view in NOMA’s Great Hall through Sunday, February 25, along with the works of six additional artists in galleries throughout the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Barkley L. Hendricks (1945–2017) was one of the great American artists of the past fifty years, with a style and vision unlike any other. He is best known for his life-sized painted portraits, largely of people of color, which give representation to and champion those in society who have largely been underserved. Working apart from any artistic group or movement, he pioneered a new way of looking at the figure in art, whether the art world was ready and willing to follow or not.

Barkley never cared for what was fashionable or considered what other artists were doing. When the majority were working with abstraction and minimalism, he turned to the figure and representation. His true-to-life portraits are stylized and emotionally stirring, unlike the clinically rendered photorealism of the era. They also reveal his rare talent for capturing and conveying the personalities of his subjects through quirky details—distinctive styles, attitudes, gestures and expressions. His honest portraits of everyday people convey the depth of his subjects’ psychology while elevating the common person to iconic status, which boldly challenged the status quo of the art world and society at large.

I first encountered Barkley’s work when I was in graduate school in the mid 1990s, reproduced in art history books by Richard J. Powell and Thelma Golden’s Black Male (1994) catalogue. His paintings were arresting, unlike anything I’d seen before, and I was unable to shake them from my mind. In the fall of 1998 I moved to New York and in March of 2000 I cold-called Barkley at his home in New London, Connecticut. I was curating an exhibition that summer at Brent Sikkema Gallery in Chelsea and I hoped that I could convince him to show his work. I reached out to a curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem and asked if she would give me Barkley’s contact information. She did, with the caveat that I promise not to tell him where I got his number. I was told that Barkley had a reputation for being kind of prickly. I assured her that her secret was safe, and I gave Barkley a call. I was unsure what to expect. Maybe he wouldn’t take my call or maybe I’d get a couple of minutes to make my case. What I found on the other end of the line was a warm, generous, funny and inquisitive person with whom I shared more common interests and experiences than I could have realized. We spoke for over two hours—about his work, about music, about our experiences in Nigeria, about Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti. At the end of the conversation Barkley invited me to visit him and his wife Susan at their home. I took him up on it the next weekend and spent the day getting to know them and the work. It was an exhilarating experience for a young, aspiring curator. Barkley contributed two large portrait paintings to my first exhibition, The Magic City (2000). We didn’t know then that it was only the beginning of a long relationship.

In 1983, Barkley painted a beautiful portrait of his wife Susan, titled Ma Petite Kumquat. It turned out to be his last large-scale portrait until 2002. Barkley was always his own man, even defiantly so. When the art world expected more of his remarkable portrait paintings, he simply stopped making them altogether. He kept producing—landscape paintings, watercolor still-lifes, mixed-media assemblages, photographs—but big portraits were no longer on the menu. That is, until he painted Fela: Amen, Amen, Amen, Amen . . . in 2002. Barkley loved Fela Kuti, the cultural revolutionary and inventor of Afrobeat music, so much that he offered to paint Fela’s portrait for the next show I was working on, Black President: The Art and Legacy of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti (2003). He was so inspired that he started painting well before I had the New Museum of Contemporary Art secured as a venue. I was blown away by the generosity of that gesture, but looking back, I didn’t fully realize the magnitude of Barkley’s action. He wasn’t just creating a new portrait, which he hadn’t done in nineteen years, for a show that may or may not happen. He was also for the first time ever, taking on an “outside” assignment, so to speak. Instead of painting people from the neighborhood, he was painting an already iconic, popular figure, albeit one who he met on multiple occasions. So he took it to a different place, with elaborate variegated leaf on the background and with painted elements that only appear under black light in a special shrine-like atmosphere. He also figured out a way to marry his love of painting with his passion for found objects, specifically women’s high-heel shoes. He painted twenty-seven pairs of heels in honor of each of Fela’s twenty-seven wives, his “queens” Fela called them, and placed them in an installation in front of the painting. The resulting work ended up being one of the most talked-about pieces in the exhibition, and represented another breakthrough for Barkley—he started painting large-scale portraits again. For that, I am immensely grateful.

Over the course of seventeen years Barkley and I worked closely together on numerous occasions, including on his painting retrospective Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool (2008), which traveled to museums in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and Houston. Up until he passed away, we were working on a selection of portraits for Prospect New Orleans, Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp. On view at the New Orleans Museum of Art, it is the largest and most significant presentation of his portraits since “Birth of the Cool,” with works ranging from 1970 to 2016. Long ensconced in private collections, the majority of these paintings have rarely, if ever, been shown in a public venue until now. But if his portraits are iconic images that inescapably foreground his influence on so many artists to come, it is less known that Barkley was equally dedicated to photography and works on paper, producing an extensive body of work that has yet to be properly explored and shared with the world.

Barkley was a pioneering spirit who defiantly went against the grain and remained true to himself at all times. He thankfully didn’t care much about other people’s opinions and he didn’t suffer fools—but he was also a thoughtful teacher, a keen observer of life, and a loyal and generous friend with a great sense of humor. His unrelenting dedication to his vision and style has deeply inspired younger generations, and he has left behind a powerful legacy. Today Barkley stands out as an artist well ahead of his time. His extensive body of work is as vital and vibrant as ever, and the full impact of his art and teaching is only beginning to unfold.

Trevor Schoonmaker is the Chief Curator and Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and the Artistic Director of Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp.