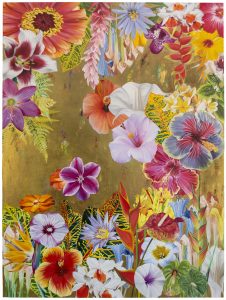

Carlos Rolón, Gild the Lily (Decadence upon Decadence III), 2016, Oil paint and 24-karat gold leaf on canvas, 72 x 54 in., Private collection, Image courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Photography Nathan Keay

On view through August 26, Puerto Rican artist Carlos Rolón’s solo exhibition, Carlos Rolón: Outside/In, explores the rich connections between New Orleans, Latin America, and the Caribbean through allusions to each region’s natural and built environments. Rolón spoke with Mellon Curatorial Fellow Allison Young about community, place, and heritage as expressed through his art.

How has your artistic practice been influenced by your upbringing?

As a child of first-generation Puerto Rican immigrants in the United States, culture is something that I personally have always been interested in. My installations are often rooted in personal memory, or inspired by music, colors, and exuberant domestic environments. I often channel ideas from my upbringing through tchotchkes, ornaments and mass-produced faux objets d’art—such as vases, light fixtures, wallpapers and textiles—which reflect a sense of “bluecollar baroque” and attainable luxury.

For example, as a child I bore witness to the ways in which immigrant households adapted to new American lifestyles through everyday items. Mirrors, in particular, adorned my family’s domiciles. As a material, mirror allows a makeshift home in Puerto Rico made from cinderblock and corrugated metal to seem larger than normal, and creates a grand aesthetic that embellishes the interiors. While triumphant, this aesthetic signals a process of adaptation and has become an integral component throughout the upcoming exhibition at NOMA.

Your art is in constant dialogue with architecture. How has this interest informed the works that will be on view at NOMA, and how might New Orleans architecture factor into the project?

My practice is informed by a postcolonial and Afro-Caribbean diasporic vantage point that is also evident throughout the cultural fabric of New Orleans. I want to bring aspects of these histories into the institution, and to help the public to feel welcomed and included. One example will be the installation Bochinche (2016), which incorporates custom marble benches surrounding a central sculpture of wrought iron fencework, ceramic, mirror, and porcelain pedestals, handmade shell macramés, and references to exotic floral vegetation. This piece harkens back to the day before smartphones and social media, and serves as a physical place for friends and acquaintances to gather, chat, and build community. This and other works respond to the wrought-iron fence work—or rejas in Spanish—seen throughout New Orleans and the Caribbean. While beautiful, these elements serve as security fences and designate boundaries between public and private. Each of these elements represents a sincere acknowledgement of the cultural identities and histories in New Orleans—Caribbean, French, African, and American.

Outside/In touches on Puerto Rico and New Orleans as specific points of reference to larger questions around race, class, colonialism, and the environment. What connections or relationships do you hope to suggest between these two locales?

One direct historical connection that will be conveyed is the Spanishcolonial discovery of gold in Puerto Rico and the Gulf of Mexico, which was facilitated by the removal of exotic tropical flora and vegetation. Enough gold was mined until 1530 to establish over four million dollars in Spanish currency. Many of the works included in Outside/In, including a series of floral paintings inspired by the vegetation in both regions, make use of real 24-karat gold leaf, generating a sense of hope and beauty as well as melancholic notes from the past. These works represent my reimagined replacement of the natural beauty that lived and breathed atop the minerals that brought wealth and abundance to colonizing cultures, contrasting the ideas of nature and territory.

Many of the works in Outside/In meditate on the ideas of personal security and perimeters. In both Puerto Rico and New Orleans, one finds a tension between inclusion and exclusion, or private and public, as well as a desire to safeguard or protect local culture and history. This process can also create a sense of seclusion or isolation.

In the course of planning your exhibition at NOMA, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico. Has this disaster informed the direction of your practice in any way?

Natural disasters are devastating, non-calculated social experiences. Maria, which was the first Category 5 hurricane to hit the island in eight-five years, is now being compared to Katrina which devastated New Orleans in 2005. Both faced a familiar cycle—loss of jobs, a weakened economy, and new diasporas leading to a decrease in local population. My goal is to convey a message for the community to embrace their past while still being present in the moment.