At center: Heihachiro Sakai (Japanese, b. 1930), Untitled, c. 1959, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, Tina Freeman Fund and funds provided by George and Milly Denegre, 2018.77

You Are Here: A Brief History of Photography and Place, on view through August 11, explores photographs of place, photographs in place, and photographs about place. The exhibition encourages visitors to think more deeply about how photography mediates their individual experience of the world and other people in it.

This curated selection of photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection begins from a bit of a paradox. Since the debut of photography in the early decades of the nineteenth century, we have believed that this medium has the special ability to share the particularities of place—virtually all of us are familiar with the sensation of viewing a photograph and sensing its strong sense of place or stating with belief, “It’s just like being there!” And yet, some of the very qualities that we associate with a photograph — flat, portable, reproducible — are antithetical to the ways that we conceptualize a place: singular, experiential, and fixed in space. You Are Here both embraces and challenges the photograph’s role as a faithful record of place, examining photography’s successes and failures in rendering, and sharing, fragments of the world. With an array of more than seventy illuminating photographs—some of which are on view for the first time—this exhibition traces a history of photography and place from the origins of the medium to the present, considering photography’s visual and material characteristics along the way.

A series of Photographer’s Perspective Gallery Talks with local photographers will take place throughout the run of the exhibition. Join us on the following dates:

Wednesday, June 19, 12 pm: Monique Verdin

Wednesday, June 26, 3 pm: Allison Beondé

Wednesday, July 10, 3 pm: Johnathon Traviesa

Wednesday, July 24, 3:30 pm: Abdul Aziz

Saturday, July 27, 3 pm: Gallery Talk with Mellon Curatorial Fellow Brian Piper

You Are Here begins with works that exemplify photography’s promise in the nineteenth century to depict places near and far with new accuracy, while also demonstrating how these kinds of photographs often provided a limited representation of the places they claimed to document. In the first gallery visitors find some of the earliest efforts to faithfully represent rural and urban England while also illustrating the entanglement of photography and European colonialism, underlining how photographs have been used to shape perception of people by providing a limited view of the places they live.

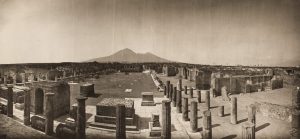

Adolphe Braun, Panorama of Pompeii, c. 1868, Carbon print, Museum purchase, Zemurray Foundation Fund, 74.174

Works like Adolphe Braun’s (French, 1812–1877) Panorama of Pompeii make clear the great enthusiasm for photographs of ancient sites in the Mediterranean and Middle East during this period. Braun’s phenomenal carbon print also shows how the technologies of photography created new ways to actually see the world. Braun made landscape photographs using a special pantascopic camera, which used gears to rotate so that a large lens would pass across a flat glass plate moving in the opposite direction, exposing just a part of the negative at a time. Prints like this one could give the landscape the appearance of being concave. New technologies like this represented landscapes in ways that could never be experienced with human eyes, changing the ways that people imagined faraway places.

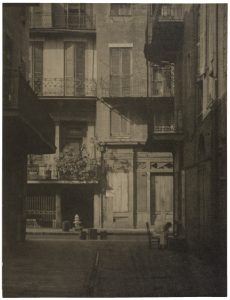

Arnold Genthe,, Untitled (Off Pirate’s Alley, New Orleans), c. 1925, Platinum print, Museum purchase, City of New Orleans Capital Funds, 76.32

13 5/16 x 10 1/4 in.

As the exhibition moves forward in time, it shifts focus to emphasize photography’s creative role over its documentary capacity, offering examples of how photographers in the twentieth century made specific and often aesthetic choices to shape our understanding. Among these photographs is as Arnold Genthe’s 1925 platinum print Untitled (Off Pirate’s Alley, New Orleans). Genthe traveled to our city in the 1920s intending to make charming views of a quaint and antiquated French Quarter. When he arrived, however, he found an already modernized city crisscrossed by wires and streetcar tracks. Genthe worked hard to exclude those elements associated with modern life by shooting in dark alleyways and courtyards. Visitors to NOMA can view Genthe’s masterpiece, printed in his typically romantic, pictorialist style, alongside other photographs of the French Quarter made at roughly the same time, but which emphasize the business of life in a vibrant city.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Man and Mirror) from Kitchen Table Series, 1990, Gelatin silver print, Promised and partial gift of H. Russell Albright, M.D., 93.558

Other photographers represent places that can take many different forms—like homes or domestic places. Several photographs of homes in You Are Here are documentary or journalistic in their portrayal, but Untitled (Man with Mirror) from Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series reveals the photographer performing one scene from an imagined day-in-the-life of an African American woman in the twentieth century. By staging these moments in a place that is generic yet specific—at a kitchen table—Weems can call on all of the political and cultural symbolism of that familiar gathering space in order to explore different themes like family life, gender, sexuality, and racial identity.

Alva Pearsall (American, 1839–1893), Formal Portrait of a Family Group, c. 1885, Albumen print, Museum purchase, General Acquisitions Fund, 82.170

Weems’s photograph is one of a number of staged, or even fictional, places mixed into the exhibition. Photographs involve other definitions of the word “place,” and You Are Here includes many of the places that photographs were both made and seen in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. An example includes the unidentified family portrait shown above, taken in the Brooklyn studio of Alva Pearsall. In this tableaux, nearly everything about the parlor setting is false, from the stairs painted on the backdrop to the dog under the chair. Pretending to be in their own parlor, surrounded by the markers of middle class life, like a piano and stereoscope viewer, the photograph essentially allows them to performing their social “place,” regardless of whether or not that picture reflects their real lives. Many of the photographs on display in the exhibition were intended to be seen in very different contexts—in this case on the mantel in this family’s home—and their presentation at NOMA invites us to consider how portable photographs are, and how their meaning might change as a result of this portability.

Rich Frishman, Colored Entrance, Tylertown, MS, 2018, Archival inkjet print, Promised gift of an anonymous donor

Other photographs included cause us to question exactly where a photographer stood when they tripped the shutter, and how the viewer might effectively orient themselves to understand what they are looking at. Without revealing any secrets, a great example of the dislocating effect of photography is this untitled work by Heihachio Sakai (see image at the top of the article), which is mammoth in more ways than one, and frustrates our ability to cite a specific place by toying with scale and pushing representations towards abstraction. The exhibition concludes with the works of photographers who explore place more conceptually, like John Divola and Ed Ruscha, raising questions about what makes a place (is it the simple act of taking a picture?) and whether or not a photograph can truly enable us to share the places that are important to us more fully. Additionally, NOMA is excited to include brand new works by photographers Rich Frishman and Jonathan Traviesa, on view in You Are Here for the very first time.

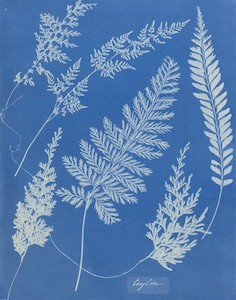

Anna Atkins, Ceylon [examples of ferns], between 1852 and 1854, Cyanotype, Museum purchase, General Acquisitions Fund, 81.385

—Brian Piper, Mellon Curatorial Fellow of Photography